Six Ideas to Rescue Higher Education

Nimbyism is killing opportunities for younger folks. Here’s how we could fix it.

College is a lubricant of social mobility, a vaccine against a creeping caste system, and a key that unlocks the American dream. Yet over the past 40 years, it’s become more difficult to access and more expensive, staying more the “same” (i.e., stale) than nearly any offering. We can scale social media platforms from thousands to billions of users, turn Porsches into SUVs, and lift billions of people out of poverty globally, but we can’t shape a college education beyond a four-year tour of auditoriums and projectors.

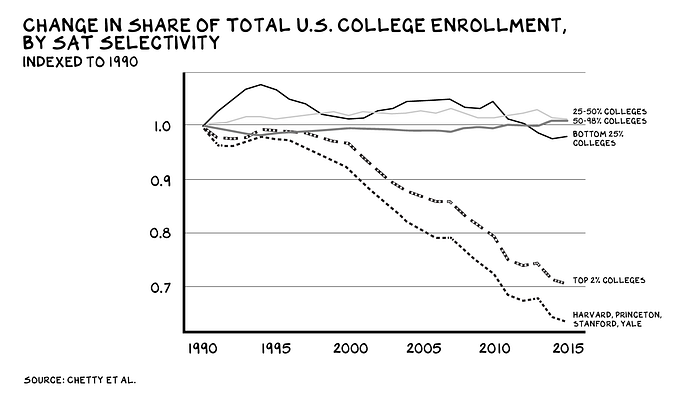

The sector is ripe for disruption. In any other industry, innovators would have moved in long ago. But higher education is different: It’s got iconic brands (Apple and Coca-Cola have nothing on Stanford and MIT), a self-policing “accreditation” system, and an unholy alliance with the financial industry ($1.7 trillion in student loan debt). So things keep getting worse. And the worst of the worst are the elite schools, who’ve doubled down on their rejectionist cultures even as their endowments have exploded. The share of the student population enrolled at elite schools has been declining for decades. “Let’s build something wonderful, so we can share it with almost nobody,” said every Ivy League President. #Gross.

A bright spot? Our great public universities. For example, the University of California, which recently set a goal to add 20,000 more seats by 2030. But the sun of UC’s good intentions has experienced a partial eclipse of Nimbyism (Nimby = not in my backyard). This town-gown dispute is indicative of the challenges facing higher ed, and our country.

Sociology 104B: Studies in Nimby

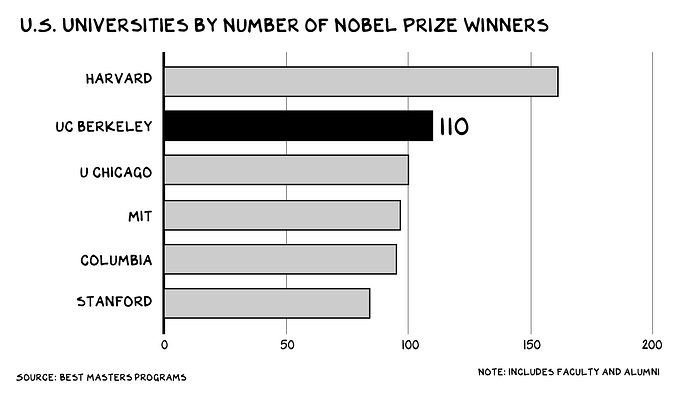

UC Berkeley has expanded its enrollment just 1.3% per year since I graduated in the nineties. More Berkeley grads is good for California, America, and the world. Berkeley boasts the second most Nobel Prize winners of all U.S. universities, produces the most Peace Corps volunteers, and is the nation’s fourth-largest manufacturer of Olympic medalists.

However … more UC Berkeley doesn’t appeal to some Berkeley residents, who like the cultural accoutrements of a college town, just not college students or the housing they need. In 2019, the City of Berkeley and a neighborhood group sued to freeze the school’s enrollment.

The city and the university cut a deal: UC Berkeley agreed to pay $82.6 million to the city over 16 years (double its previously planned payout) to account for the increased burden on city services, and the city dropped its lawsuits and endorsed the university’s growth. Seems reasonable.

Except that the neighborhood group wasn’t satisfied with 80 million bucks. It continued its lawsuit and won — relying on an environmental law from the 1970s that observers say was never meant to police population growth, let alone higher education. The kicker? The enrollment “baseline” year is 2020, when enrollment cratered, thanks to the pandemic, so the freeze will require the university to cut 3,000 students (2,000 undergrads and 1,000 graduates) from its anticipated 2022–23 enrollment. To minimize the reductions, Berkeley will tell more than a thousand new undergrads they have to take their first semester online and require another 600 to defer until 2023.

Economics 316A: Churn, Baby, Churn

The median sale price for a home in Berkeley is $1.6 million, nearly four times the national average. And prices keep going up (12% in the last year). Berkeley homeowners are the beneficiaries of a long economic boom — a boom that came in no small part courtesy of UC Berkeley’s graduates and researchers. On the other side of the backyard fence, UC Berkeley and its students are the arbiters of change, the potential for a better future. But what we witness incessantly in America is people who’ve benefited from our innovation economy pulling the ladder up behind them.

In 1940 a 37-year-old had a 92% chance of earning more than their parents did at the same age; a 37-year-old today has a 50% chance. It’s never been more expensive to buy a home. Since 1989, young people’s wealth relative to their income has declined, while older people’s has grown. Put another way, the old are getting richer and the young poorer.

And while the younger generation is down, we boomers continue to kick them. Today, two-thirds of jobs require a postsecondary education and training, but college costs have increased 150% faster than average earnings of 22- to 27-year-olds since 1980. We spend 7% of our federal budget on children — the only OECD nation that spends less on kids is Turkey.

Old people don’t want change. They want scarcity and ossification, because it protects what they have. Young people are different — they want churn and growth, so they, too, can go buy a nice house and turn into Nimbyists.

In Berkeley, it’s likely California will carve an exception to the law for the UC system, but housing for students is still in critically short supply, and next year there will be another battle, another lawsuit. We can’t scale America’s colleges one lawsuit at a time.

College towns are victims of their own success, bringing character and culture that benefit residents who register appreciation — and then want to create a scarcity ecosystem that will further buttress their wealth and lifestyle. University leaders need to adapt to a scarcity mindset in which companies, graduates, and homeowners all want less access once they have theirs.

Some ideas…

Urban Planning 485A (Senior Seminar): Thinking Outside the B(erkeley)ox

You know who would welcome 50,000 of California’s brightest students and most-accomplished researchers? Fresno. Or Davis. Or Bakersfield. Any town north of Sacramento or east of Los Angeles. Governor Newsom, if you want an unlock, build a campus in Fresno. Build a high-speed rail system from Fresno to the Bay Area and weave the tech industry into a new community.

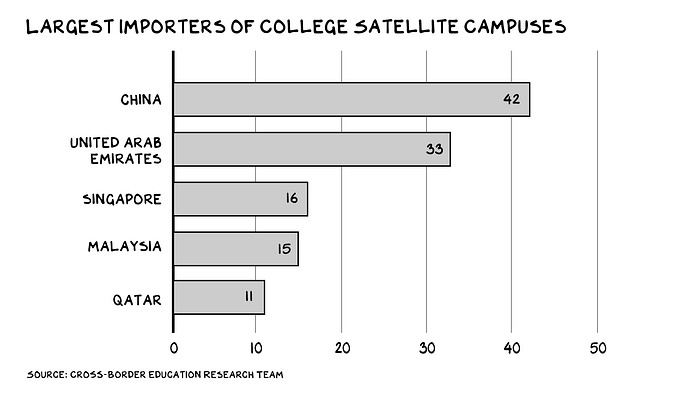

That’s just a start. Our elite private schools have become enamored with satellite campuses, but they’re mostly fond of the checks autocratic regimes are willing to write to wrap themselves in the comfortable blanket of academic credibility. Building a satellite campus in Abu Dhabi (my employer’s innovation) is arbitraging the brand, not expanding the franchise. Same goes for most executive education, where a mid-level manager gets her company to pay $30,000 for six days across two on-campus “immersions” during a “multi-modal” experience so she can post a Chief Digital Officer certification from Kellogg/Penn/Columbia on her LinkedIn profile. Big Ed(ucation) is beginning to make Big Tech seem noble.

The elite should be building campuses in places that would welcome the investment instead of filing lawsuits — cities such as Albuquerque, Cleveland, Tulsa, etc. This would diversify the elite’s currently cloistered experience, worldview, and politics. Meanwhile, doubling a city’s degree production increases local human capital levels by 7%. Household incomes in college towns are 7.4% higher than in noncollege towns. Jesus, what could a second MIT do for Mississippi?

I wrote in New York magazine in 2020 that the truly elite universities would leverage their brand equity and technology to scale and consolidate the market. I could not have been more wrong. A rejectionist, Hermès-style positioning is their drug of choice, and they are speedballing the sleet.

Lean into the online-hybrid model. We tried this during Covid, and it worked … sort of. The missing ingredient from college in 2020 was socialization. But there’s no reason to believe that would disappear if we moved classes online. In 2011, 87% of college students lived off campus, and that didn’t stop them from going to bars, dating, and forming special-interest groups. Nineteen-year-olds aren’t good at much, but they’re great at getting their hearts broken, getting drunk and high, and having unprotected sex … at scale. Life finds a way. We tend to speak in binary terms: traditional experience or all online. It will be a mix. If we took 33% of our classes online (and we can), we could increase capacity by 50%. But this can’t be an afterthought or an emergency measure — distance education done well requires investment and new skills.

Here’s a pedestrian fix: Go the way of Dartmouth — quarterly.

Most college campuses sit near-empty for three months a year, an egregious waste of capital investment. But Dartmouth’s quarterly calendar means undergraduate classes continue throughout the summer. This makes sense; summer vacation is a relic we inherited from previous generations whose buildings didn’t have AC and who needed their kids to come home to work on the family farm.

A key to increasing seats may be to transfer the costs of college from students to corporations. The average cost of hiring an employee is $4,000. Why not lump those recruiting costs into a subsidy partnership with a university and provide early access to young talent? This would let talent-hungry companies build a pipeline from campus to HQ. Transfer the costs and burdens of career centers to the companies that benefit from them.

Some companies are already doing it: Starbucks started teaming up with Arizona State University in 2015 — its applicant pool increased by more than half a million, and 63% of new hires expressed interest in the partnership.

Could we put higher ed on the blockchain? Could a university rethink its relationship with the community and tie access to a token? Something like this: Stanford mints 100,000 tokens and auctions them to the public. Each Cardinal Coin gives the bearer unique access to the Stanford community: a vote on major policy changes, entrance to sporting and cultural events, and a seat in any Stanford degree-granting program (subject to minimum standards). Every January 1, another 3,000 coins — no more — are minted and sold at auction. Say, the first trade of the coin offering is at $1 million to $10 million a coin. If you have two kids, you’re looking at savings of nearly $500,000 in tuition alone, and the access would create a bidding war for a store of value that would also attract speculative investors.

What would guaranteed admission, tuition, alumni events, community access, etc. be worth? Let’s be conservative and peg the value at the lower end, $1 million per coin. This translates to $100 billion in new capital, with another $3 billion in revenue coming in every year thereafter. That quadruples the endowment, increases investment income, and lowers costs (admissions and development departments would no longer be needed). Unrivaled capital to open satellite campuses, invest in the next generation of distance learning tech, or just build more dorms.

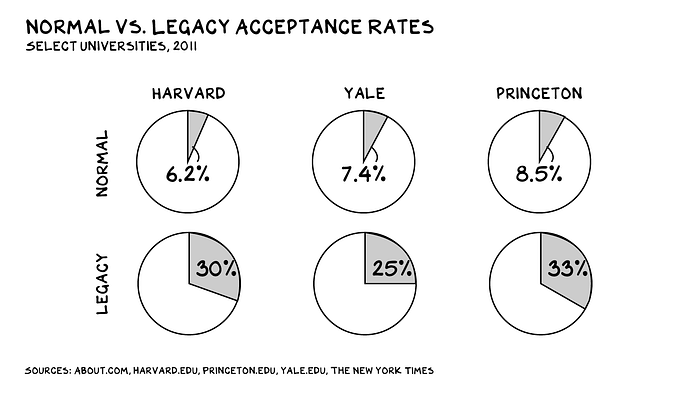

Would this turn Stanford into the exclusive preserve of the wealthy? Elite universities already are. The wealthy game the system with multimillion-dollar donations (aka the Kushner Krush) or try to bribe someone (Aunt Becky). The Cardinal Coin, putting this all out in the open, could facilitate diversity and merit-based aid. Philanthropists could (will) purchase coins and assign the rights associated with them however they choose — to kids from low-income households with strong academic achievement, or to unremarkable kids raised by single mothers who show promise but could never get into a school that now only admits 9% of applicants, vs. 74% when I applied. #GoBruins.

This was a suggestion from Stig Leschly.

Any naval personnel meeting basic requirements can show up to SEAL tryouts, but the program starts tough and gets tougher — admissions by attrition.

What if an elite university had an adjunct campus that implemented the academic equivalent of SEAL training? No admissions department — whoever makes it through the first semester is admitted. Wouldn’t this also create fierce, resilient, strong capitalist warriors? Warriors chosen for their skills, strength, and grit vs. who their parents are?

The tip of the spear for America, higher education, has become markedly less American over the past several decades. We need massive investment and a rejection of the rejectionist and scarcity mindset to return higher ed to its rightful place as an upward lubricant for kids whose parents aren’t rich and who haven’t peaked at 17. We also need to expect more from university leaders, who’ve had little incentive to innovate or rock the boat. Technology is not the key element for the requisite innovation; class traitors are. Deans and chancellors who push back on faculty and alumni and the dangerous notion that we are luxury brands, not public servants.

Also, Berkeley homeowners, stop it. Just stop it.

Life is so rich,

P.S. I started Section4 to give people greater access to business education and the network that comes with it. We’ve got plans to expand that access even further — look out for big news from us next week.